G-parity

In theoretical physics, G-parity is a multiplicative quantum number that results from the generalization of C-parity to multiplets of particles.

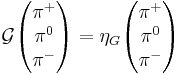

C-parity applies only to neutral systems; in the pion triplet, only π0 has C-parity. On the other hand, strong interaction does not see electrical charge, so it cannot distinguish amongst π+, π0 and π−. We can generalize the C-parity so it applies to all charge states of a given multiplet:

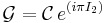

where ηG = ±1 are the eigenvalues of G-parity. The G-parity operator is defined as

where  is the C-parity operator, and I2 is the operator associated with the 2nd component of the isospin "vector". G-parity is a combination of charge conjugation and a π rad (180°) rotation around the 2nd axis of isospin space. Given that charge conjugation and isospin are preserved by strong interactions, so is G. Weak and electromagnetic interactions, though, are not invariant under G-parity.

is the C-parity operator, and I2 is the operator associated with the 2nd component of the isospin "vector". G-parity is a combination of charge conjugation and a π rad (180°) rotation around the 2nd axis of isospin space. Given that charge conjugation and isospin are preserved by strong interactions, so is G. Weak and electromagnetic interactions, though, are not invariant under G-parity.

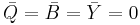

Since G-parity is applied on a whole multiplet, charge conjugation has to see the multiplet as a neutral entity. Thus, only multiplets with an average charge of 0 will be eigenstates of G, that is

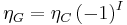

In general

where ηC is a C-parity eigenvalue, and I is the isospin. For fermion-antifermion systems, we have

.

.

where S is the total spin, L the total orbital angular momentum quantum number. For boson–antiboson systems we have

.

.

See also

References

- T. D. Lee and C. N. Yang (1956). "Charge conjugation, a new quantum number G, and selection rules concerning a nucleon-antinucleon system". Il Nuovo Cimento 3 (4): 749–753. doi:10.1007/BF02744530.

- Charles Goebel (1956). "Selection Rules for NN̅ Annihilation". Phys. Rev. 103 (1): 258–261. Bibcode 1956PhRv..103..258G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.103.258.